The European Mink

/in In The Spotlight, Meet The Carnivores /by Stefanie SillerThe European mink (Mustela lutreola) has a long, slender body with a short tail. The weasel-like mammal is usually dark brown to black, with a thin white patch around the mouth that sometimes continues down the neck. It is this contrasting marking that distinguishes them from the similar American mink (Mustela vison).

The white markings on the upper lip distinguish the European mink from its American cousin. Photo by EfAston

As a semi-aquatic species, they have a dense, short coat with a water-repellent undercoat to insulate them in the water. Excellent swimmers, their paws are webbed to help them swim, dive, and hunt underwater.

European minks are largely nocturnal, solitary animals. They have a wide range of prey from small mammals, fish, crustaceans, insects and more. They occupy large ranges, always near fresh water. A female mink may stay near a den within her territory, while males venture much farther.

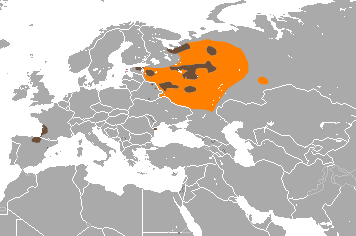

The European mink is one of Europe’s most endangered mammals. In 2011, the species was upgraded from Endangered (EN) to Critically Endangered (CR) on the IUCN Red List. Their range has been reduced by at least 90% since the mid-19th century. The minks suffered from overexploitation for their fur in the early 20th century, leading to a weakened population. In 1926, the larger American mink was introduced to Eastern Europe to be used for its more valuable pelts. The American mink’s presence put great pressure on food and habitat availability, pushing the European mink out of much of its range. Additionally, human expansion and increased land use, as well as hydroelectric developments and water pollution has led to a fragmented population.

Currently, the European mink population exists in isolated regions in Russia, with small introduced subpopulations in France and Spain. Most of these groups are in rapid decline and low density. There are many captive breeding programs working to establish new European mink populations and add new genetic diversity to existing groups. Efforts are being made to restore and designate protected areas and maintain standing ones.

The Alexander Archipelago Wolf

/in Meet The Carnivores /by Stefanie SillerThe Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni), also known as the Island Wolf, is one of the rarest wolf subspecies in the world. Endemic to southeastern Alaska, it has been isolated from other North American wolves for millennia, and is both morphologically and genetically distinct. It is smaller and darker than other wolves, and it comprises a significant portion of grey wolf (C. lupus) genetic diversity in North America.

The Alexander Archipelago wolf is also behaviorally and ecologically distinct from other wolf populations. For instance, this subspecies is unique in its habit of feeding nearly entirely on a single species, the Sitka black-tailed deer. Both the Alexander Archipelago wolf and the deer depend on old-growth forests for survival. In particular, the Tongass National Forest, the nation’s largest national forest, is crucial habitat for the wolf and the Sitka black-tailed deer. It is home to some of the largest remaining stands of old-growth, temperate rainforest in the world, as well as other endemic species like the Prince of Wales Island flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus griseifrons) and a distinct lineage of Mustela ermine that depend on these old-growth stands.

However, recent increases in logging pose a major threat to the Tongass National Forest and the wildlife within. Reduction of old-growth forest diminishes crucial winter habitat for the Sitka black-tailed deer, leading to declines of the wolf’s most important prey. The impact of the timber projects, combined with the past 60 years of logging, is increasing the deer’s susceptibility to predation, hunting, and weather. Furthermore, high density of logging roads provides increased human access, which is directly related to high wolf mortality and illegal take of wolves.

In particular, the 2014 Big Thorne timber sale by the U.S. Forest Service has paved the way for the largest logging operation in the Tongass Forest in 20 years. This project allows for over 148 million board feet of timber to be logged from 8,500 acres of old-growth forest. Furthermore, in July 2017, the USFS put forth a proposal for the POW LLA Project that would consist of an additional 200 million board feet of logging of old-growth forest on Prince of Wales Island.

The population of the Alexander Archipelago wolf residing on Prince of Wales Island is particularly threatened. Making up potentially 30% of the wolves in southeast Alaska, these wolves are bo th geographically and genetically isolated from other populations, and constitute one of the most at-risk populations of the subspecies. Since the mid-1990s, the population of Alexander Archipelago wolves on Prince of Wales Island has declined from about 250-350 down to an estimated 89 individuals. This population is therefore of crucial conservation interest.

th geographically and genetically isolated from other populations, and constitute one of the most at-risk populations of the subspecies. Since the mid-1990s, the population of Alexander Archipelago wolves on Prince of Wales Island has declined from about 250-350 down to an estimated 89 individuals. This population is therefore of crucial conservation interest.

Despite these risks, the Alexander Archipelago wolf and the Prince of Wales Island population have been repeatedly denied endangered or threatened status under the Endangered Species Act since 1993. As a result, populations of the subspecies have substantially declined since the mid-1990s under the continued pressure of logging, unsustainable harvesting, and increased human access via roads. And despite a recent suit, the courts have upheld the U.S. Forest Service’s Big Thorne timber sale, putting at risk not just the wolf, but the numerous other endemic and unique species that reside in southeastern Alaska. We must act now to save the Alexander Archipelago wolf and its vanishing habitat.

.

Sri Lankan Jackal

/in Meet The Carnivores /by Stefanie SillerThe jackal is a cunning and resourceful species found all over the world, and the Sri Lankan Jackal (Canis aureus naria) is no exception. The Sri Lankan Jackal is one of thirteen subspecies of the Golden Jackal, and as you can guess by its name, this jackal lives in Sri Lanka and southern parts of India. The jackal is slightly smaller than a wolf, with smaller legs, body, and tail overall. Its back is covered with black and white fur with a brown background. This beautiful canine is mysterious, curious, and agile. However, don’t be fooled by its good looks. This jackal is a skilled hunter and scavenger, carnivore and herbivore. As a pack animal, they can organize and take down large prey. The pack also waits for other predators to make a kill, fill up, and then scavenge the rest of the food. The jackal has a wide range diet that consists of small animals including rodents, birds, mice, young gazelles, reptiles, and also fruits. This diet allows the jackal to thrive in varying niches that include forest, grasslands, semi-urban, rural, and arid areas.

Since the jackal has adapted and thrived in different habitats, it is currently listed as “least concern”. However, there are still concerning threats impacting the Sri Lankan Jackal. Human overpopulation in India constantly pressures wildlife through habitat loss, industrialization, agricultural and livestock expansion. In addition, Sri Lankan locals fear that the jackals will transmit rabies and other diseases to themselves and their domesticated dogs. Another threat is the trade of jackal’s pelts and tails, but the Wildlife Protection Act hopes to minimize this. Conservation efforts mainly target educating communities on how to coexist with these intelligent canines and decrease hostile actions towards them.

As urban development increases in Sri Lanka, the rich biological community continues to be threatened. The S.P.E.C.I.E.S. project hopes to understand the carnivores in Sri Lanka that are threatened or have the potential to be threatened through surveying the current status and future of carnivore species. Learn more about our project in Sri Lanka here.

Rusty-spotted cat

/in Meet The Carnivores /by SPECIESThe rusty-spotted cat (Prionailurus rubiginosus) is one of the world’s smallest cat species. At a mere 2-4 pounds (1-2 kilograms), it weighs about the same as a couple of bags of sugar. This feline is only found in India, Sri Lanka, and was recently discovered in Nepal.

One of the world’s smallest felines, the rusty-spotted cat, is about half the size of a domestic cat. Photo by Tambako the Jaguar/ Flickr CC

It gets its name from the rusty colored spots that cover its grey coat, while its undersides are white with dark spots. This small feline dines on critters in the trees, including rodents, frogs, insects, small birds, and reptiles. The rusty-spotted cat has a limited range, but its habitat is quite diverse. For example, the rusty-spotted cat is found in the rain forest and mountain forest in Sri Lanka, but resides in dense grassland in India. This elusive cat uses the forest and vegetation to stay unseen as it is extremely shy, making it a rare sight indeed. This has made researching and monitoring it an almost impossible task.

As this species is so rare, it is hard to estimate the population size and threats it faces. However, it is known that land fragmentation and heavy agriculture have impacted this species the most. According to the IUCN Red List of threatened species, these threats have pushed this species from Near Threatened in 2015 to its current status of Vulnerable.

The rusty-spotted cat is protected in its range in India, Sri Lanka, and Nepal where hunting and trade is illegal. In order to truly help the future of this species, increasing research and monitoring is the only way to understand the threats to this mysterious wild cat. While it is no larger than a house cat, its role in its ecosystem is much larger, and to save it in the wild we must understand it better and protect its forest home.

S.P.E.C.I.E.S. is undertaking a conservation programme in Sri Lanka with our partner Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society. Learn more about this project here.

Save

Snow Leopard

/in Meet The Carnivores /by SPECIESNative to the high mountains of Central Asia, the snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is as elusive as it is beautiful. Its white-grey and spotted coat blends perfectly with the snowy environment it calls home. Built with powerful hind legs, snow leopards can leap six-times the length of its body and traverse its steep landscape easily.

Globally, there are only around 4,000 snow leopards left in the wild. These enigmatic cats are frequently killed in retribution for attacks on wildlife. Their habitat used to be filled with their natural prey that includes bharal, blue sheep, ibex and marmots, but competition with agriculture has led to declines of their prey. Because of this, snow leopards now prey on domestic livestock, and in some areas, domestic animals make up 60% of their diet.

Between 200 and 450 snow leopards are lost every year due to retaliatory killings. Other threats to their survival include hunting for the wildlife trade, where their furs are highly sought after, and their bones, teeth, and claws are used for traditional medicine.

Snow leopards are found in 12 countries: Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Conservation efforts are underway across their range, but a lack of cross-border cooperation is cited as a hurdle to ensuring the species’ survival.

In Nepal, snow leopards inhabit an area approximately 13,000 km2 in size. The Api Nampa Conservation Area, in the west of the country, may provide an important location for conserving the species as the area acts as a corridor, connecting populations in India and Southern China.

A typical Snow leopard habitat in the Langtang National Park with Langtang glacier in the back drop.

Currently, little is known about the Api Nampa population, and filling this knowledge gap is essential to understanding the threats snow leopards are facing. To this end, S.P.E.C.I.E.S. and the Biodiversity Conservancy Nepal are planning to launch a project in the region to study the Api Nampa population.

Gaining critical information about the Api Nampa population will allow high human-leopard conflict areas to be mapped and conservation strategies developed to reduce this conflict. You can help us conserve this crucial snow leopard population by making a donation today.

Learn more about our Api Nampa Snow Leopard Conservation Project.

Asiatic Wild Dog

/in Meet The Carnivores /by SPECIESAsiatic wild dogs (Cuon alpinus), or dholes, have a bit of a reputation. They suffer a fate similar to that of wolves in North America; they’re often hunted due to the perception that they are livestock killers. Along with the loss of their natural habitat and disease transmission from domesticated animals, this bad reputation leaves the dhole endangered in the wild.

Despite their diminutive size, dholes are smaller than medium-sized dogs, they can take down prey that is up to 50 times their weight, such as samba deer or boar. They are pack animals and hunt prey in groups of five to ten, although their numbers were said to reach beyond 50 in the past.

Adults’ coats are a reddish-brown colour with a bushy, black tail, while their pups are born a dusty black colour, taking the colour of their parents once they are three months old.

Living in places that are inhabited by bigger, stronger predators such as tigers and leopards, the dhole has come to hunt effectively as a pack. Scouts will lead the way while the main pack follows up and takes down the prey. Dholes do not suffocate their prey with a vice-like grip like tigers do, rather they take bites, bring it down, and begin eating immediately, often while their prey is still alive.

In this video you can watch as a tiger attacks a pack of dholes. Tiny in comparison to the tiger, the dholes skip lithely away and appear to come back to pester it. Dholes are sometimes killed by tigers, and historical reports suggest that tigers have been killed by dholes, although this has never been confirmed.

There are between 4,500 – 10,500 dholes in the wild; only around 2,000 of these are mature individuals capable of breeding. They are understudied and largely unknown, even in the conservation world. But they are known to use many different ways of communicating and make use of a highly distinctive whistle as a way of gathering their pack in the forest areas they call home.

S.P.E.C.I.E.S., through its Western Ghats Conservation Project, is working to conserve the dhole in India. The project aims to identify the main threats to their survival in the Western Ghats, along with tiger and leopard populations. Once these threats are identified, conservation action will be taken through community-awareness and human-wildlife conflict mitigation efforts.

The binturong

/in In The Spotlight, Meet The Carnivores /by species1The binturong (Artictis binturong) is summed up by its nickname; the bearcat. With long cat-like whiskers, a long bushy tail, a thick coarse coat and a penchant for living in trees, the species is quite unique. Despite having a fairly wide distribution (the binturong is found in Borneo, Nepal, Java, Northeast India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand), it is rare across its range.

Very little is known about the binturong. It is an omnivorous species and will eat just about anything, although it is said to have a particular affinity for the strangler fig. Their love of the strangler fig also plays an important role for the wider ecosystem as they disperse the seeds, allowing important regrowth. Their long tail can act as a fifth limb, allowing them to move easily through their forest habitat. This strong and sturdy tail is also important as the species is said to mate high up in the trees. But as for its other behaviour and its wider role in the ecosystem, little else is known.

Across its range, the binturong is threatened by loss of its habitat due to agricultural expansion, and hunting for the pet market, traditional medicine, and as a food source.

S.P.E.C.I.E.S is currently working to conserve the binturong, and it is one of our focal carnivore species. Information is being gathered on the species to fill in important gaps in our knowledge. Key questions such as how the binturong is affected by the expansion of agriculture and the loss of primary forest, and which areas within its range may act as strongholds for the species. are currently trying to be answered.

The Javan Fishing Cat

/in Meet The Carnivores /by species1In 2008, the fishing cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) was declared “Endangered” by the IUCN. This was due in part to the extreme lack of records for the species despite wildlife surveys across much of its purported distribution. It is also due to the rapid disappearance of sensitive freshwater and coastal habitats across south Asia. Fishing cats are distributed unevenly across their range, with many populations isolated. Most isolated are those on Java, where the only recognized subspecies of fishing cat occurs more than 2000 km away from the next nearest population .

In the mid-1990’s a survey of otters on Java recorded signs of fishing cats at a number of locations along the western part of the island. Although the findings of this survey characterized the status of the Javan fishing cat as “critically endangered”, this urgent call for action has been met with silence over the past 20 years, as no specific strategy for protecting the cat has ever emerged.

Given that during this time Java’s coastal ecosystems and wetlands have suffered dramatic changes due to intensive development and a soaring human population, it is imperative that the status of the Javan fishing cat be re-assessed. Its unique genetic and evolutionary context relative to other fishing cats, and the serious threats it faces, likely makes this cat the most endangered on earth.

S.P.E.C.I.E.S plans to conduct the first thorough assessment of the status of the Javan fishing cat, which is probably the most endangered cat in the world.

The first objective is to conduct semi-structured interviews in seven human communities across western Java to assess familiarity with fishing cats and document records. We will also distribute educational brochures to promote public awareness about the uniqueness of Java’s fishing cat, and how to report observations. Based on the results of these interviews, we will conduct sign surveys in potentially suitable habitat to record further evidence of fishing cat presence. We will also identify threats to areas where evidence suggests cats are present, and propose a strategy for their mitigation. Our primary goal is to use the information we collect to assess the Javan fishing cat’s status, and inform the Indonesian government and conservation community as to immediate conservation actions needed.

Rarest cat in the world? Assessing the Status of the Javan Fishing Cat from Experiment on Vimeo.

The Clouded Leopard

/in Meet The Carnivores /by species1The clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa) is one of nature’s shyest creatures. The smallest of the big cats, they prefer to remain hidden and out of sight. This presents significant challenges when studying the species, and as a result, much of their behaviour remains a mystery.

Their range includes the Himalayan foothills of Nepal, into Southeast Asia and China, and a population exists in the southeastern parts of Bangladesh. There is also a separate species, the Sunda clouded leopard (Neofelis diardi), found only on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo. Both species are considered vulnerable to extinction by the IUCN.

Deforestation and the wildlife trade present the greatest threats to the clouded leopard. They prefer closed forest and dwell mostly in primary, undisturbed forest, although they have been found in secondary forest in some locations. Forest areas where they are found are currently facing some of the fastest rates of deforestation around the world. They are also hunted for their body parts and uniquely patterned coat, which is covered in distinctive cloud-like markings.

Read more S.P.E.C.I.E.S.’s work on the clouded leopard at Project Neofelis.